Wind, gravity, and a few other factors thrown in. That’s what you get when you leave the comfort of the 650-yard range and venture out into the desert to shoot 1000 yards.

You might imagine that finding a range in the city is hard enough. That’s certainly true. Even out past the edge of the city, most ranges taper off around 600 or 650 yards. Chris had been getting too comfortable with those distances, so we needed to find a stretch of land to give him a bit of a challenge. Fortunately, Southern California has a pretty good patch of desert that calls it home.

If we’ve learned anything about shooting in the desert, there’s always three constants: constantly shifting wind, constantly wobbling mirage, and sunlight. Between the months of May and September, you can generally expect to lose a lot of water-weight to the sun. The dry air was going to help the bullets fly, but it’s not quite meant for us humans.

Preparation

Cartridge

Leading up to the planned desert day, Chris worked on a new load for the 6.5 Creemoor rifle. It’s a Defiance Deviant Action in a KRG Whiskey 3 chassis. The 6.5mm Creedmoor rounds are comprised of once-fired brass, 41.1gr IMR 4451 powder, and Hornady Match 140gr Boat-tail hollow point bullets. (We also had a few factory loads, one for the 6.5 CM and one for the .308 Win, though those weren't as fun to shoot)

In the lead-up to this load-out, Chris set about to narrow down some accuracy nodes and choose a speed, weight, charge, and depth for the distance. (An accuracy node is a point where the powder load and bullet weight come together for maximum precision. More powder could mean more speed, but also lowering precision - until the next node, where the harmonics all work out again).

The first step was to pick a bullet and seat it to a proper depth to feed into the rifle, just to start shooting. With the starting depth confirmed on the Hornady Match 140gr BTHP, it was time to start playing with powder. Making 3-shot batches every half grain of powder, he filled cases with 38-42 grains of IMR 4451. This step took the longest - have you shopped for powder lately? Firing 3 shot groups, he checked for group sizes for tightness and the velocities for consistency.

At a few different charge weights - and velocities - the rifle and cartridge come together to work well. These nodes of precision are spread throughout the range of powder weights, and will vary based on your bullet, action, barrel, and numerous other factors. The nodes he identified in these test loads are places where his individual rifle functions best with this bullet and powder.

The fun thing about designing your own hand load - by the time you’ve settled on your potential favorite combination, you may have already shot out the barrel. Time to start over!

Nodes exist with smaller charge weights and lower speeds. This translates into less kick, which isn’t something we’re worrying about with such a heavy rifle and light bullet. Instead, speed is the name of the game. The quicker the bullet cuts through the air, the less time it’s hanging in the wind’s purview. The weather in late May called for winds of 10-15mph, though we’d been out with switching winds of 40mph. Anything’s possible! The goal was to get the bullet going around 2700 fps or faster to keep the hang time low.

A node was identified around 41 grains that could work to deliver the speed and precision that the shoot called for. By changing the powder charge in 1/10th grain increments and the bullet depth by a few thousandths, he developed a few more loads to really hone in on the high-speed node. Eventually, a half-dozen variations later, he settled on 41.1 grains and an overall cartridge length of 2.850” (+/- 0.002”). Speeds of ~2707fps, standard deviation of 10fps.

Target

Over on the spotting scope side of things, mirage was the real concern. At even our normal distance of 650 yards, mirage can stop you from seeing everything but the splash of dirt (on a miss) or dust (on a hit). Mirage is strongest when the land and air have the widest temperature difference. We wanted to start the long drive in the early morning to beat the city traffic, putting us in the desert in midmorning. The land would be warming, but the air would already be up at 80 degrees and on its way to 95. By the end of the shoot in late afternoon, the sand would be hot enough to fry an egg while the air could only toast bread. We’d be starting the morning with a moderate and well-defined mirage, then ending the shoot with a turbulent and roiling mirage. Throw in some wind, and good luck seeing anything at all.

Watching other shooters contend with great distance gave us an idea - balloons. Shooters like Gunfather Precision have balloons on the edges of their steel targets. When the shockwave reaches out from the impact or the fragments from the bullet’s jacket splash on the target, the balloon pops. Perfect indicator that can be seen from very far away.

One issue - we didn’t want to have to haul a heavy steel target (and stand!) up and down the side of a sandy desert hill in that weather. Instead, we opted for a lighter steel flywheel covered in balloons. We couldn’t count on the splash from the bullets breaking against the thinner flywheel, but we could count on balloons to pop when they were hit directly. Four balloons covered the face of the target, keeping within the 0.5 MIL (18”) expected width at 1000 yards. Behind the target, we fastened an 18” circle of cardboard to record the hits in the expected area.

Off to the side, we also brought a separate target for fun. Last time we went out to the desert to shoot at this distance, we had brought a freshly painted white target. A white target on sunny, tan sands is almost impossible to see. Lesson learned. This target is a ½ size IPSC man target (½ MIL tall, ¼ MIL wide). Painting it orange for this trip, we decided to bring it along too. Bullets would break against the front of this thicker steel plate, so we taped a balloon to his head to show the impacts.

Supplies

When packing for a normal range day, you’re going to want to bring everything that you might need. Sometimes there’s a fellow range-goer that has a tool you forgot. Out in the desert, you’d have more luck finding a forgotten tool in the sands than you would another shooter that brought what you were looking for. Making and sticking to a pre-shoot checklist is key, even down to the target color.

Shooting supplies:

- Rifle

- Ammunition for the rifle

- Magazine for the rifle

- Bipod

- Scope(s)

Shooting accessories

- Sandbags

- Prone pad

- Target frame, paper

- Target stand, paper

- Orange flywheel

- Orange ½ IPSC

- Target stand, steel

- Rangefinder

- Spotter scope

- Spotter scope tripod

- Labradar (optional)

- Labradar stand (optional)

- Cleaning equipment

- Tools and tool tips for all fasteners

- Spare screwdrivers

- Staple gun

- Spare consumables (targets, staples, zip ties, etc)

Filming Equipment

- Camera

- Lenses

- Batteries

- Memory cards

- Protective sun cover

- Phone-eyepiece adapter

- Charge pack

Ancillary “Stuff”

- Water (big bottle)

- Water (small bottles)

- Food

- Snacks

- Easy-up awning

- Ice

- Cooler

- Lens-cleaning equipment

- Trash bags

- A big wooden brick

- Flashlights

- Spare tire, patch kit, jack

Starting the Shoot

After driving out and finding the right turnoff, we headed deep into the desert. No cell signal, cars, or paved roads in sight. At the spot where we normally go, there’s a clear patch of dirt just adjacent a curve in the dirt road. One person waited in the car while the other person marched out across a dry floodwater path in 100 yard increments. Range to the car, wave, wait for the car to pull up. Repeat 10 times.

By the 900th yard, we left the car and set out on foot, keeping an eye out for a raised hillside that could serve as a target backstop. With the height of some of the creosote and dry brush, we also wanted a hillside to help lift the target above any potential blockages. Home base sat atop a hill about 5 feet above normal ground level, so a target on another hill would provide a perfectly clear line of sight. We found the appropriate hill around 1020 yards away, and went another 30 yards up the slope to ensure the target was at a good height while retaining a backstop. If we hit 10 feet off in any direction, we’d be able to see the splash of dirt. The two targets were placed 20 feet apart to prevent accidental hits, offset by 10 feet of depth.

The balloons were placed. The stand was weighed down with rocks. Time to get dialed in for 1050 yards.

Confirming Ballistics

The loadout for the day focused around the 6.5mm Creedmoor, though we also brought a .308 Winchester rifle. A wonderfully weighty MDT ACC chassis holding a Remington 700 action. No muzzle device at the end of the floating barrel. It kicks twice as hard as the 6.5. We hadn’t worked out an appropriate load for it, and the factory loads had 1 - 1.5 MOA of accuracy. The rounds go transonic a moment before 1000 yards, adding a bit of tumble to the ballistics calculations.

We went armed with 3 scopes for the 2 rifles, and planned to reach out to 1050 yards with all of them. The first step then was to make sure the rifles were starting off at 100 yards with the expected precision and speed they were meant to display. We went back out into the sand to plop down a board of paper targets at 100 yards.

Two of the scopes were PR5 5-25X26 scopes, not yet available for purchase at the time this article is being written. One 5-25 was meant for the 6.5 Creedmoor and was dialed in for 100 yards on that rifle. The other scope went on the .308 Winchester and was similarly sighted in at 100 yards. The turrets were re-indexed to stop at “0” on the 100 yard zero for elevation, and the estimated “0” for wind. As we would find out later, wind direction was the biggest concern.

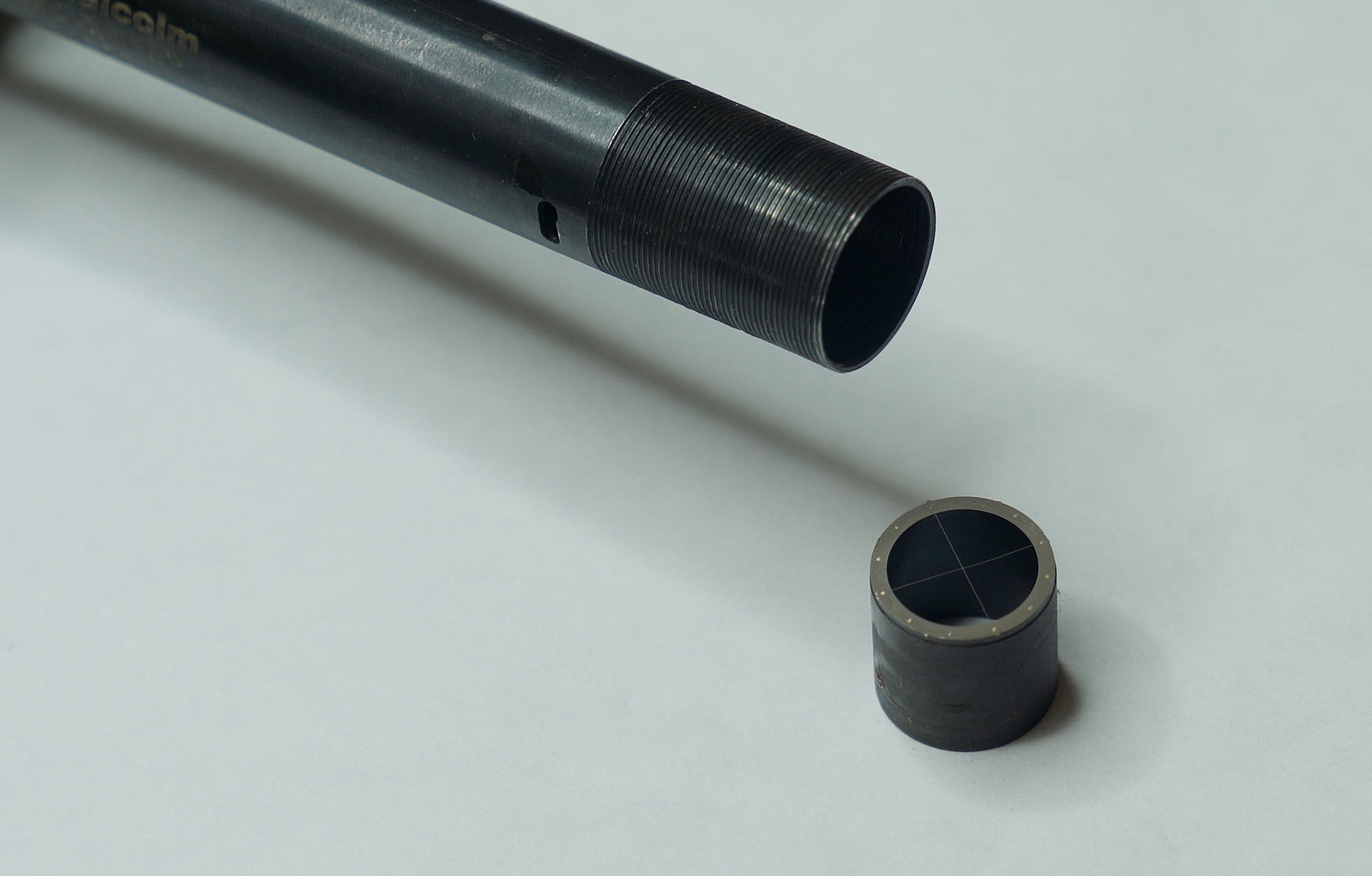

The M1200-XLR, a 6-24X ART scope, was also set on the 6.5 CM rifle. This scope had been dialed in at Desert Marksmen during one of our normal range days, but had since been unmounted from the rifle. This scope is built with Jim Leatherwood’s Automatic Ranging Trajectory system, giving it the ability to adjust for the rifle’s ballistics from 300-1200 yards or meters. Chris had also previously dialed in the CAM to the ballistics at Desert Marksmen, confirming the accuracy out to 650 yards. The desert location had different atmospherics, mostly in terms of pressure. The temperature was a bit higher, and the humidity the same. 92F, 2250' Elevation, 28.0 inHG, 10% Humidity, 10-15 mph Winds. CAM setting of 580 for our load when shooting at Desert Marskmen.

The M1200 needs an initial zero of 300 yards (or meters) to utilize the ranging feature, unlike the PR 5-25 which can be zeroed at any convenient distance. We didn’t want to walk the paper target out to 300 yards, so Chris trusted a repeatable mounting procedure to ensure the scope’s zero would remain the same. The integrated mount for the M1200 has a length of picatinny attachment. This picatinny rail slot has a recoil lug that can be pushed up against the back of a picatinny rail tooth, reducing potential slippage and mounting at a repeatable location. By placing the recoil lug against the same tooth on the 6.5’s rail, the scope ended up pointing the rifle remarkably close to the target when we went straight out to 1050 yards. More on that a little later.

Reaching Out

After hitting the 100 yard paper with all the scopes (and even the M1200 with a known offset from center), it was time to reach out. The first step was finding the target. Either target would be on the small end for human sight, and there was a lot of desert to find them in. We began to pick out visual cues to locate the targets; go to the top of the mesa, move along to the left edge, come straight down to the berm, place the rim of the berm near the top of the sight picture, scan left. Eventually, this was shortened to; scan left until the curve in the flood runnel, keep going left with lip of berm at top of sight picture. It took a bit of time to initially find the target, but proper recoil management kept us on target thereafter.

The M1200-XLR on the 6.5 Creedmoor was the first combo up to bat. Chris turned the CAM to the appropriate distance, then split the magnification ring away from the calibration ring. This allows the ART scope to have magnification control independent of the CAM elevation adjustment. The scope is second focal plane, and has true reticle values when at 20X. Holding off for the wind required a repeatable reticle measurement.

The first shot was a bit high and a bit to the right. Wind was blowing from left to right for most of the distance, though was generally right to left nearest to us. The bullet was cutting through the left-tending wind and getting caught up in the right-facing wind. The air was a little off from how we predicted, and we didn’t want to adjust the CAM setting from its Desert Marksmen setup. Instead, we turned the CAM’s elevation compensation to a slightly different value, and held off for wind.

A few more shots, and then we saw two balloons pop. Another shot, and the other two popped. Chris shot out the rest of the mag, and we drove down range to check out the target. The cardboard backing confirmed the hits that popped the balloons. After replacing the balloons, it was time for me to take a few shots as well. The hold for the wind was switching between 0.5 and 1.2 MIL to the left. With the target at 0.5 MIL in width, that made the game a little tricky.

After the M1200 got a few good hits, it was time for both rifles to try out the PR5 5-25X56 scope. This is a 5-25X first focal plane scope. The scope could be at any power and still give an accurate hold. We kept the scopes around 20-22X. Just enough to keep a wide field of view and still get some accurate shot placement.

With the intensity of the mirage, the balloons were necessary to confirm most hits. Misses were generally easy to see, provided they hit the dirt. If the bullet bounced off a rock in just the right way, there’d be no splash to mark it as a miss. The spotter scope was equipped with a fixed 33X eyepiece, which had MOA markings inside. This was an easy way to judge wind holdovers and still get a good idea of misses. By dialing the focus of the spotter to a middle distance, it was possible to get a fairly accurate read on the wind between 2-10 mph. More mirage makes target visibility go down, but wind visibility go up!

Towards the afternoon, we figured out another aspect of desert winds on the flat land: velocity change. When the wind was to our backs, the bullet flew flatter. Not a lot, but enough to move the bullet half a target or so in elevation. When the wind was coming from our front, the bullet would fall short. A wind over the left shoulder might blow the bullet a bit to the right, but it would also cause the bullet to hit higher. Holds for wind started to be on the diagonal, down-left or down-right for wind from the back, up-left and up-right for wind from the front. Wind directly to the side got the largest wind holdover, but no elevation change.

Even though we figured out what was happening before we figured out why, we stuck to a simple rule: “Trust the bullet.” This rule was handed down to us from Leo, the man who set us on the path of handloading and continues to let us know how little we know. Even if all your calculations seem correct, wait for the bullet to confirm. You may think you’ve dialed exactly right, but there may be some other factor you haven’t accounted for. Take a shot, trust the bullet.

End of the Day

By the time the sun was working its way down the mountains, we were aiming to get on back to civilization. Long story short, but don’t be stuck in the desert in the dark with a flat tire and no cell service. We grabbed the targets off the hill and our cases from the sand. The targets needed a fresh coat of paint, and the brass would get cleaned and sorted before being reloaded for the next range day. Trash was packed out, water was finished, and it was time to hit the road.

In the course of getting the rifles dialed in and confirming wind shifts, we went through about a dozen balloons. It wasn’t worth the effort to go out to the target every time to replace them, so eventually we started to trust the dust of a missed shot to tell us when we were off. Comparing some before and after shots, we got around 18 hits at 1050 yards over the course of the day. The wind shifted every direction except 4 and 5 o’clock, so the day turned into an active and fast-paced lesson on wind holdovers. I can’t recommend it enough.

Leave a comment (all fields required)