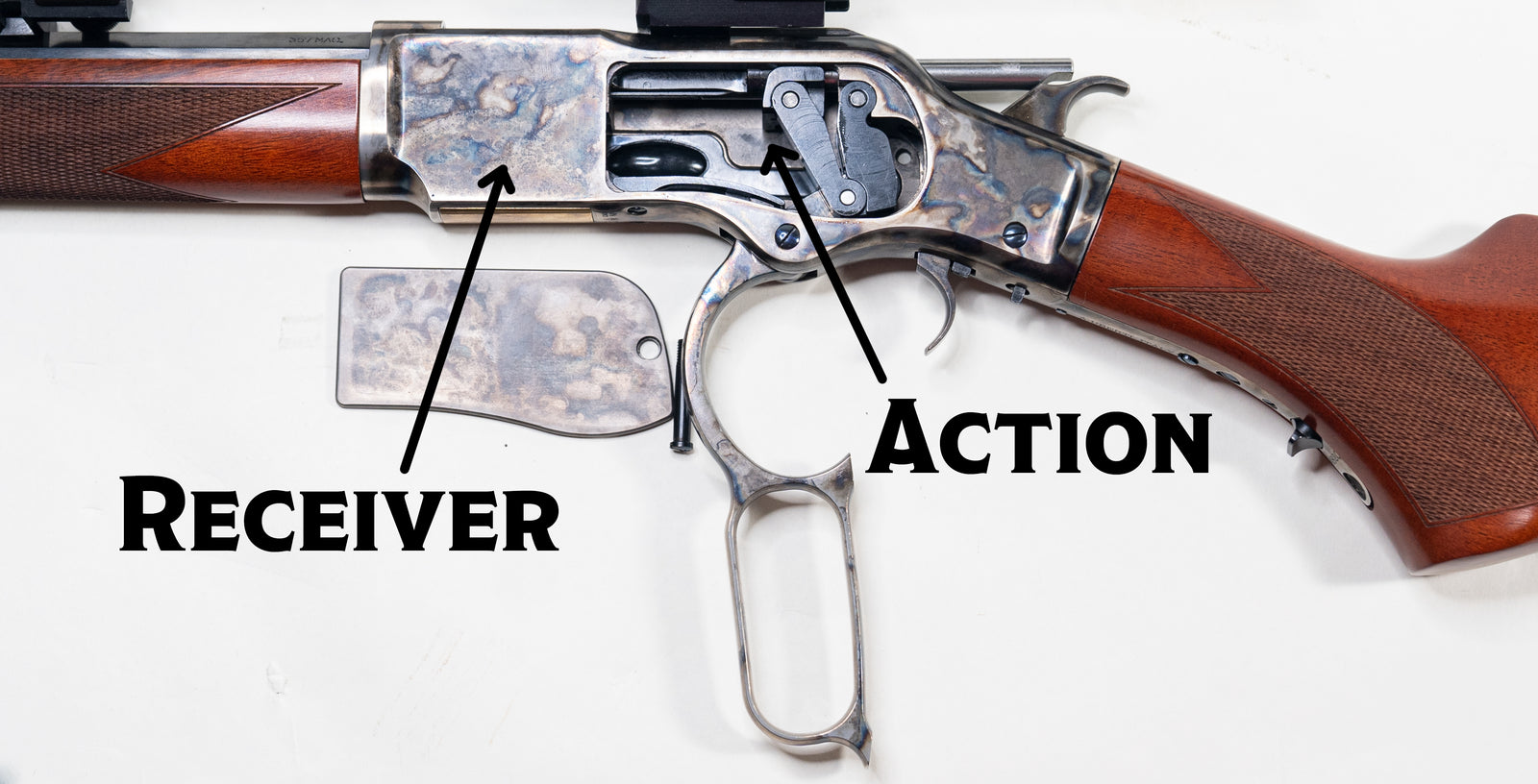

In a nutshell; the action is the portion of the rifle that performs the action of firing the round and ejecting the cartridge. The action is the mechanical structure responsible for loading a cartridge into the chamber, firing, and ejecting a cartridge. Let’s just say - this is literally where the action happens. Make all the puns you want.

The action is housed in the receiver. The receiver is a metal shell that holds all the surfaces the action might move along, as well as using pins and screws to fasten the action in place. The receiver joins up with the barrel, making sure the bolt closes firmly against the chamber to prevent any escape of gas. Ideally, the receiver and barrel will not shift in relation to each other during firing, which would throw off your alignment and ballistic path.

A Winchester 1873 with its side plate removed to show the action. The receiver is the (unmoving) metal shell that contains the action. The action is the set of moving parts hidden inside the receiver.

The receiver is fixed into the stock by more screws and pins. The stock is the place where you’ll hold on to the overall rifle, so it too should not shift in relation to the receiver. You’ll find out more about inletting and bedding in another article, which are means by which a receiver or action might be more precisely and securely fastened into a stock.

The hollowed out portions of the stock where the rifle’s receiver and barrel will rest, along with a long slot for the trigger mechanism to fit.

There are many types of actions, most of which you’ve probably heard of. Each type of action handles the loading, firing, and ejection processes differently. The goal of each action is the same - to cause the round to fire. Some actions may not load or extract the round without a little extra effort on your part. Due to the way in which each action handles the force of firing, different actions work well with certain rounds or may not work at all with others. The most common risk is in loading a round that is too powerful for a particular action. Always follow the manufacturer’s recommendations in regards to cartridge pressure to ensure proper function of the rifle.

Below are some of the more common names for actions. Some of these styles will have further variations. So much variety exists that the whole of another article will be devoted to actions alone. Each of the designs varies in how it cycles the action, or performs one full set of the functions that an action performs. These actions, after firing, are: unlock the action, extract the spent case, eject the spent case, cock the hammer or firing pin, load a new cartridge, lock the action.

- Lever action - The sort of mechanism you’d see in an old cowboy rifle. These are identified by their large, looping handles down behind the trigger. The loop is pulled away from the rifle and then back into place by hand, moving all the parts of the action through mechanical linkages. After each shot, the lever must be opened and closed fully to eject and then chamber a round. Typically, pushing down on the lever will handle ejecting the spent case and cocking the hammer, while closing the lever will handle chambering a new round and locking the bolt or breechblock in place.

- Bolt action - A massively popular design for precision shooting. After a round is fired, a small handle on the side of the rifle must be lifted, pulled back, pushed forward, then turned back down by hand. Each stage of motion performs a function: unlock the bolt, eject the case and cock the hammer, chamber a new round, re-lock the bolt. This design can take quite high amounts of pressure and has very few parts that can break.

- Semi-automatic - A wide field of designs that handle an equally wide variety of ammunition. Semi-automatic actions will fire once with each pull of the trigger, and then cycle the action using the energy of that shot. Many mechanisms have been built to utilize either the high pressure gas, the pressure exerted on the spent case, or the force of the recoil itself. Due to the mechanical constraints of each design, certain semi-auto actions will handle different sizes and pressures. For each action, there will be specific rounds that simply cannot work.

- Single-shot - The single shot action may be the only design simpler than the bolt action. Just as in semi-automatic actions, a number of single-shot designs have cropped up. The falling block is quite common among late 19th century rifles. In it, a small lever behind the trigger is manipulated down and up by hand. This in turn moves the breechblock out of the way to remove a spent case or into position to hold a new cartridge in place. The round must be inserted by hand and the spent case removed after firing. Due to the solidity and simplicity of the parts, single-shot rifles can withstand some of the highest pressures and largest rounds. Another design is the break action, which hinges open just behind the barrel. When open, a new round may be inserted or a spent case removed.

- Automatic - This is a rare action in the civilian world. Once the trigger is pulled, the rifle will continue to fire round after round until it runs out or jams. A single pull of the trigger can empty your magazine. Typically, automatic rifles are seen in the hands of the military. They’ll have an option to select the rapidity of fire, between automatic, semi-automatic, and safe. For this reason, they’re also known as select fire rifles.

Four of the common rifle actions laid out. Once you’re familiar with the components to look for, understanding each rifle becomes much easier.

For most of these actions (excluding the automatic), pulling the trigger once will fire one round. To fire again, you need to let pressure off the trigger and get another cartridge ready to fire. Different actions require a different amount of effort to get that next round ready.

The specifics of each rifle-style’s action will be discussed further on in another article. This segment is here to help get you familiar with the general terminology and parts, as all actions need to serve the same purpose - getting that bullet going.

Actions are sometimes described by their length, or the length they’ll have to move to accommodate the cartridge. Different cartridges have different lengths, measured out to the tip of the bullet. Some are quite miniscule, while others are many inches long. These countless varieties have broadly been separated into four general action lengths:

- Mini action - The shortest cartridge lengths, under 2.3 inches. Most commonly, the .223 Remington, used in the AR-15, will come up as fitting a mini action.

- Short Action - Cartridges between 2.3 and 2.8 inches. Though the .308 Winchester is considered a fairly strong and highly capable cartridge, it fits into the short action category. With a bullet installed, the .308 Winchester sits around 2.8 inches in overall length.

- Long Action - Cartridges between 2.8 and 3.34 inches in total length. Historically speaking, the .30-06 Springfield is one of the most popular cartridges in this category. Its length sits at the maximum, around 3.3 inches in total depending on bullet weight and nose shape.

- Magnum - Cartridges over 3.34 inches. If you’ve seen an action movie, you’ve likely heard of the massive .50 BMG “Browning Machine Gun” cartridge. It fills out a whopping 5.45 inches of total length, and delivers the kinetic energy to match.

Comparing the action lengths for two common cartridges - the powerful .308 Win and the diminutive .22 LR.

Most rifle actions will have an integral component known as a bolt. The bolt is a sturdy piece of metal shaped like a conventional bolt. It slides forward and backward on guiding surfaces inside the receiver. The bolt has a very hard front surface that presses against the head of the case, sealing it into the chamber. It’ll also have a small claw or lip, meant to grab onto the rim and extractor groove of the case. Finally, it will have a firing pin that is meant to strike the primer. The bolt cocks a hammer as it moves back, or else holds the firing pin back against a spring. Much like on a revolver, where the hammer happens to be easily visible, any internal hammer is meant to strike the firing pin sharply. It hammers the firing pin into the primer when the trigger is pulled. The hammer or firing pin is held back by the sear, a small edge of metal that keeps the hammer from moving until the trigger pulls the sear out of the way.

Depending on the type of action, you may be responsible for moving the bolt manually by means of a small handle (as in a bolt action). In other actions, the bolt may move and cycle the action for you - otherwise known as a semi-automatic action. When moving on its own (or in a few special bolt actions), the bolt sits as part of another component, known as the bolt carrier group. The bolt carrier group handles much of the effort of a semi-automatic action, potentially providing a piston for air to hit, or just a heavy carrier for the rest of the bolt to ride in while resisting momentum.

A semi-automatic rifle’s bolt carrier group sitting alongside a bolt action rifle’s bolt. The BCG (bolt carrier group) lacks a handle, while the standard bolt relies on it.

Leave a comment (all fields required)