If you’ve ever asked, “Am I moving my point of view when I dial? What does impact L or U mean? What is being adjusted in there?,” then it’s time to learn about turrets.

What are Turrets?

Turrets are round, squat knobs of a cylindrical shape. The sides will typically be marked with an index in the same measuring system used for the reticle. An MOA-marked reticle will typically have MOA-marked turrets. A MIL reticle will use MIL-marked turrets. Old scopes may have a MIL-marked reticle and MOA-marked turrets, which is simply confusing.

For modern scopes, the turrets are attached to the body of the scope at the turret block, roughly in the middle length of the scope tube. There should be two turrets - one to adjust the elevation (up-down), one to adjust the windage (left-right). This is not far off from an etch-a-sketch control system.

In addition, you might find turret-like dials to control the reticle illumination and scope parallax. They are not standard in all scopes, and aren't important for this particular article.

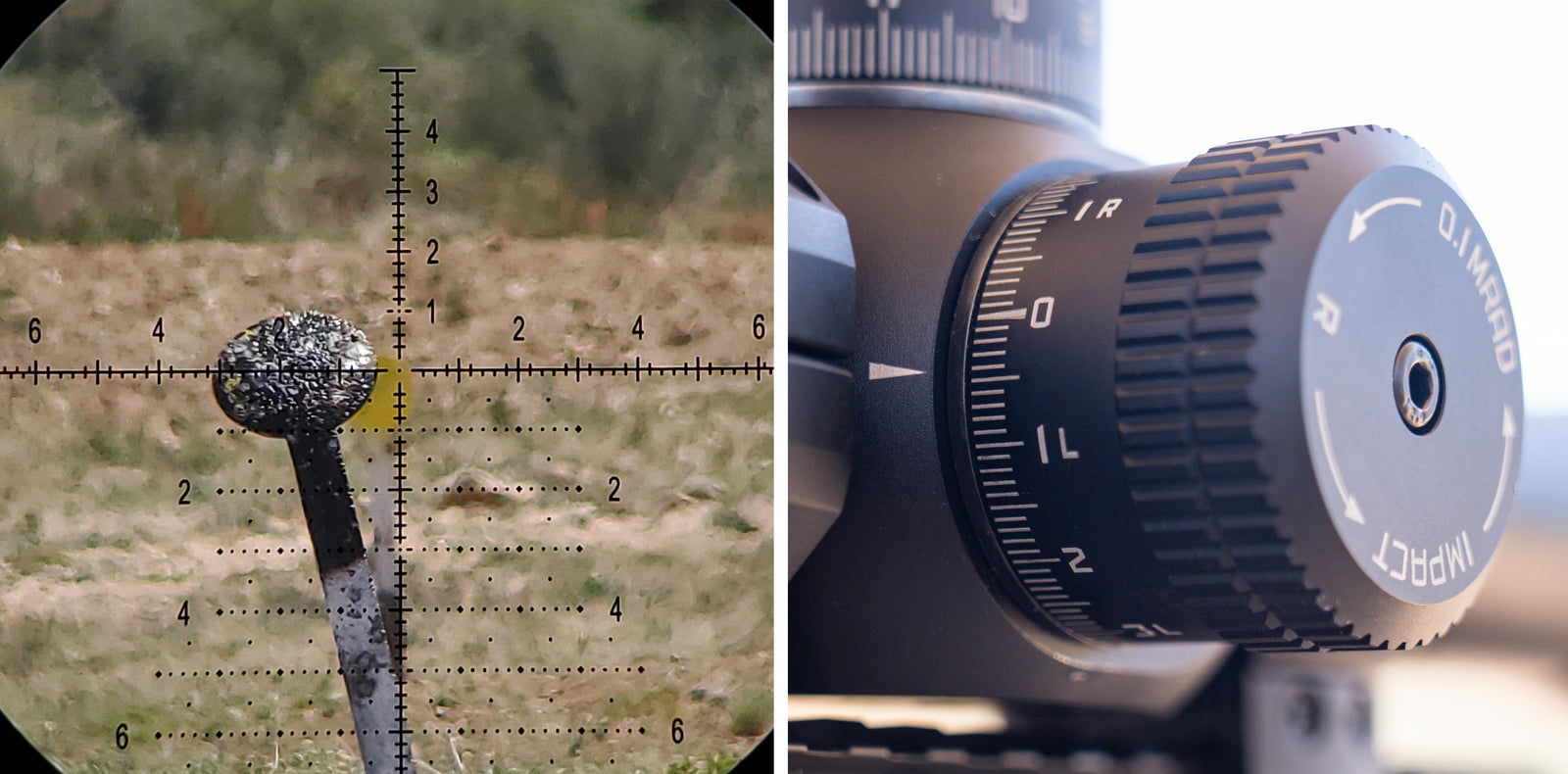

Turrets on a scope, each marked with an index and adjustment direction. For the elevation turret shown at the top of the scope, turning counterclockwise will move the point of impact up.

What Does Dialing a Turret do?

When you dial a scope, you’re actually physically turning the turret. This turret connects to a plunger inside the scope, raising it and lowering it when the turret is turned. This plunger pushes the erector unit, changing the angle at which it points. This changes your field of view by the corresponding angle you have dialed. To maintain pressure against the bottom of the plungers, a spring inside the scope applies constant pressure to the erector unit from the opposite side.

What Does a Click Mean?

When you turn a turret, there should be a noticeable click. You’ll feel the click with your hand, and hopefully hear it with your ears. Each click will adjust the erector unit’s angle by a specific amount - in modern scopes, ¼ MOA or 1/10 MIL per click, depending on the scope. Some people will record their adjustments by noting the number of clicks instead of the actual angular adjustment. This is known as counting clicks. If you know the value of each click, you can easily convert to angular measurements. For example, 4 clicks of ¼ MOA each becomes 1 MOA of adjustment. 2 clicks on the same turret would equate to ½ MOA.

Turrets will have a visual index on the side, in case you’ll be adjusting by reading the numbers on the side. If you’re making a large adjustment, counting clicks is considerably slower than simply looking at the index and dialing to the correct number.

When you turn a turret to adjust your aim, you’re not changing anything about the firearm. Instead, you’re adjusting where your scope is looking. The reticle stays right in the middle of your view, so you’re technically adjusting where the reticle is pointing. Most modern turrets adjust the point of impact. This means that if you dial up 1 MOA, the bullet will appear to impact 1” higher at 100 yards. All you’re doing is changing where the scope is aiming in relation to the rifle - and by extension, how you have to point the rifle to be on target.

Crosshairs aiming off center from the target. If the bullets are hitting at the center of the target, the impact could be brought to the center of the crosshairs by dialing 2 Mil to the right.

How do Turrets Work?

Not all clicks are created equally. Clicks happen when a small, spring-loaded plunger or ball bearing dips into a detent inside the turret. The detents are spaced repeatedly around a circular metal surface, giving the turret a specific number of clicks per full revolution. Each time you hear a click, the plunger is clicking into the next detent.

If the detents are poorly machined or the plunger is worn out, the turret may have mushy clicks. This means that each click is difficult to discern, either by sound or by feel. Counting clicks will become very difficult, especially in high-stress and high-noise situations.

Especially worn detents or a weak erector spring may cause the erector unit to settle slightly out of place. This is known as backlash, and requires the turret to be dialed again until the erector unit settles into the right position.

The best turrets are those with firm, noticeable clicks and no backlash. Backlash can cause your adjustments to become untrustworthy. You can’t trust a scope if you don’t know where it’s aiming. Mushy clicks will still move the erector unit to the correct angle, but will require a visual confirmation of the adjustment value. At the end of the day, mushy clicks can be dealt with, but backlash is unacceptable.

A look under the hood on an old scope turret. On the left, the turret is in its normal functional state. On the right, the turret has been disassembled. The ring with the detents has been set on its side to show the underside. Normally, the underside sits flat atop the surface with the ball bearing. Each detent is one click, and those clicks are reflected on the index outside the turret.

Capped or Uncapped Turrets

Turrets may be covered by a screw-on metal cap. Turrets that can use a cap are known as capped turrets. Some turret blocks are not built with the necessary threading for caps to be used. These turrets are known as uncapped turrets.

Capped and uncapped turrets are designed a little differently. If your turrets are designed to stay uncapped, they’re meant to be adjusted easily and often. The turrets will be built larger, with easily graspable surfaces. In contrast, capped turrets are designed to be easily hidden under a cap. Capped turrets are meant to be adjusted infrequently.

Depending on your intended use and your distances, you may have to dial your scope up and down quite a bit. Depending on the windiness and how often you prefer to use holdovers, you may dial left and right quite often. The long and short of it is - if you expect to use holdovers to aim (instead of dialing), or you just prefer shooting at one distance for a long period of time, capped turrets are your best bet. You’re less likely to bump the turrets and accidentally dial in an adjustment.

If you’re shooting at multiple distances and you have to rapidly adjust your turrets, you’ll want turrets that are uncapped. In this case, it’ll also be useful to have larger, easier to read turrets with more defined clicks, so you can have an easier time keeping track of your adjustments in the heat of the moment.

Two different scopes, the left with capped turrets, the right with uncapped turrets.

Locking Turrets

Some uncapped turrets will have a turret lock. This is a way of locking the turret in place, so accidental bumps do not change your dialed setting. However, this lock would need to be disengaged to change your settings, and could slow down your shooting in a fast-paced competition.

Instead of a lock, some turrets have a mechanism that prevents you from dialing below your zero. These types of limits (also known as zero stops) are more commonly found on tactical scopes. While the zero stop must be disengaged when initially zeroing, once set, a shooter can dial multiple adjustments and quickly return to zero without the risk of losing the zero.

Turrets are not always marked as having a lock or zero stop. Instead, you’ll find this out by using the scope or reading the instruction manual. Some scopes will also have differences between the elevation and windage turrets - for example, an elevation turret with a zero stop and a windage turret without the zero stop.

Re-Indexing a Turret

Some turrets may also have the ability to re-index. Let’s pretend you’re finally zeroed in at 100 yards - the bullet is hitting right where the crosshair is aiming. You’d like to save your settings, so that you can return to the 100 yard zero quite easily. Re-indexing the turret is the process of loosening the turret (so you can move it without adjusting the erector unit), turning the turret so that the index on it lines up in the way that you want, then tightening it down. Commonly, once a good zeroing point is found, turrets are re-indexed so that the ‘0’ value lines up with the indicator line.

Most shooters will re-index the elevation turret for their normal zeroing distance. You could do the same for the windage turret, but it’d be best to wait for a no-wind situation so you can find the actual center.

Leave a comment (all fields required)