When I first started looking into the history of Metal Butt Plates, I didn’t quite know what I might find. Pretty quickly, my research turned toward the development of rubber recoil pads. Everything I was reading was highlighting the simple fact that shooters of ‘ye olden times’ had precisely the same concerns - and inventiveness - as the shooters of today. In the case of metal and rubber butt plates, the concern was one I’m sure many of you are familiar with: high recoiling long arms hurt less when there’s a cushion for your shoulder.

Our story picks up in 1874 with the Silvers Company of England, and ends around 1930 with a name I’m sure many of you are familiar with: Pachmayr. A bit of a spoiler alert: These bruised-shoulder shooters solved the serious concerns of considerable kick, even way back then.

Through ingenuity and a desire to shoot without flinching, they went through every variation of recoil pad you can imagine. From the first solid rubber pads bolted onto the backs of shotguns, they worked the shape and structure to increase its effectiveness. They tried springs, they tried air. They had buttplates with adjustable height and carvable shape, set atop spacers to perfectly fit the stock to the shooter. In essence, the shooters of old did exactly what shooters today are still doing - find a way to make recoil manageable.

I hope you enjoy this walk through the turn of the century, as the advent of shotgun cartridges enabled people to shoot high-recoil long arms more often than ever before.

If you have an old rifle - especially one that fires something strong - you’ve probably got a steel butt plate on it. Every time you fire, you can feel just how hard that steel plate can be.

So why the heck did the shooters of strong old rifles stick with steel?

As it turns out, they didn’t.

Stocks throughout firearms history have been made from wood. Wood is a wonderful material to work with. It can be shaped to perfection, finished and fitted precisely, and is generally all-around good looking. The only problem - it does not always respond well to stress.

The butt of a rifle encounters many more surfaces than just your shoulder. A drill rifle might get slammed into the ground. A combat rifle might get slammed into an enemy. A regular rifle might fall onto a rock. However it happens, a plain wood stock might splinter or split. Pretty early on, people figured out that protecting the butt of the stock would make your life easier.

Nobody wants a splinter recoiling into their shoulder.

To protect the butt of the rifle, butt plates were invented. I’m not entirely sure which material came first from the following mix, but I’d have to guess leather. Leather made a great protective material for both you and the rifle. It might even provide some cushion. However, some manufacturers and militaries wanted something sturdier.

They turned to brass, iron, or steel for buttplates. To your shoulder, these metals feel largely the same. To manufacturers of the time, brass was the easiest to work with. Later wartime changes made drop-forging steel a pretty quick process.

Throughout all this, users of long-arms could agree on one thing. More shots, more recoil, more shoulder pain. Around the 1860s, shotgun cartridges were out in the world and becoming commonplace. These cartridges caused a lot of grief at the back of many metal-faced stocks, but people were still having fun trap shooting with new, lightweight shotguns.

Only a decade or so into this new shotgun craze, sore-shouldered shotgunners were seeking solutions to their shooting woes. By 1874, they had one.

The Silver Company of England crafted the “Anti-Recoil Heel Plate - The Silver’s Safety Pad,” though today it would be called a recoil pad. Their recoil pad featured a thin and hard rubber underlayer, fastened to a thicker vulcanized rubber cushion. It was essentially a thick rubber block stuck onto a less thick rubber strip, screwed onto the back of the stock. The rubber chunks would then be shaped to join up with the stock.

As it turns out, the design didn’t need much improvement. You can still buy similarly constructed recoil pads made by S. W. Silver for about $50 today.

Once it became known that you could attach a rubber cushion to the back of your rifle, plenty of people wanted to do things their own way. By 1915, this cushion craze had spread to America in the wildest way.

James Day patented a design in 1914, and allowed the Jostam Manufacturing Company to produce the pads. W. R. Jorgenson of the Jostam Company was awarded a patent of his own in 1915. Frank Hawkins patented a pad under his own name in 1919. Their big change from the Silvers pad, as simple as it sounds, was the inclusion of holes. These holes were cut laterally through the main chunk of rubber, giving the pad some space to compress.

By and large, many people agreed that this was a good idea. They agreed so quickly that the companies D&W, Funkes, Huntley, Perkins, Tryon, Grieb, Hawkins, and Jostam all started producing similar pads right around the start of World War I. The product was simple. It was relatively easy to manufacture. It was finished and shaped by the customer or their gunsmith. And, perhaps even more importantly, recoil pads were quite customizable.

Just for fun, let’s look at these early customizations.

In 1909, just two decades after Silver’s Recoil Pad hit the market, J. S. Johnson patented a spring-loaded recoil plate. It was a slip-on design that attempted to use springs under a steel plate, instead of rubber. Ultimately, it didn’t turn out to be too popular. Still, you can’t fault him for trying.

In 1913, John Perkins was awarded a patent for an adjustable-height butt plate. A narrow metal track was screwed onto the back of the rifle, almost like a spacer. The butt plate could be moved up and down on this track, then fastened in place with a central screw. Looking at the patent drawings, it seemed like the plate was curved to fit the shoulder and could be adjusted up or down ⅓ of the plate’s height. It wasn’t very well cushioned, but later cushioned pads would be improved by his concept.

In 1916, just two years after James Day’s patent, P. J. Krueger patented an air-filled recoil pad. Using a combination of leather and rubber, the pad contained an oddly shaped air pocket that could be refilled by a hidden valve.

By 1920, Goodrich was selling a multi-layered multi-rubber pad with a permanent air cushion inside. By joining a firm rubber base to a soft rubber exterior, the pad formed an air pocket that did not have to be refilled. As a total side note: Roughly 17 years after this, Goodrich would also invent the first synthetic-rubber tires for automobiles. Much like Maxim’s silencer for the Springfield 1903, an inspiration for mufflers, this is yet another firearm advancement that made its way into automobiles. I just think that’s neat.

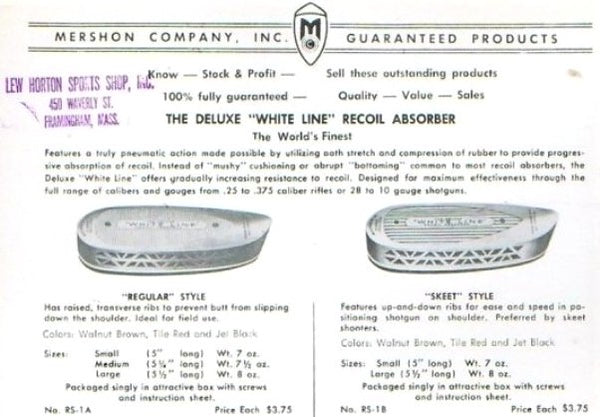

Getting back to recoil pads, however… one of the last advancements in the field came from the Mershon company. A particular Mershon advertisement from the 1930s describes the problem, and their solution, incredibly well. “Features a truly pneumatic action made possible by utilizing both stretch and compression of rubber to provide progressive absorption of recoil. Instead of mushy cushioning or abrupt bottoming common to most recoil absorbers, the Deluxe White Line offers gradually increasing resistance to recoil.” You may be wondering why a company that seemed to perfect the recoil pad isn’t around in the modern era. That would be because the company changed its name to that of their founder and the pad’s inventor: Frank Pachmayr. Though presently owned by Lyman, Pachmayr’s recoil pads have been in use by shooters for nearly a century, with little change from the original design. At present, the Deluxe White Line pads mentioned in the 1930s advertisement are available for around $40.

As it turns out, shooters in ye olden days had the same concerns about recoil that we do today. Namely, that they didn’t want it to hurt, and that they also didn’t want to give up shooting. The classic designs for recoil pads haven’t changed all that much. The solutions that worked back then still work just as effectively today: replace the metal plate with some somewhat squishy rubber, and you’re in for a much gentler experience.

Even the name of Jostam’s original Pad reflects this shared experience - it was known as “the Jostam Anti-Flinch Pad”... until they released the “No Kick Coming” pads. Other companies would market their pads with similar ideas. The ‘Red Head’ recoil pad was stamped with the words, “No Jolt.” Perkins released the “Shock Absorber.”

I’ll leave you here with a newspaper advertisement for the Winters Recoil Pad, which encapsulates quite perfectly the many shared problems of shooters across the years. “Those who have acquired the annoying habit of flinching from the recoil of the gun when firing at an inanimate target or live bird can be greatly benefitted by using Winter’s leather covered pneumatic recoil pad. It is so different from other recoil pads that a trial convinces one of its great value. It is made by a practical gunner and fully guaranteed to give satisfaction. It requires no pump and is easily regulated. The rubber part is covered with a fine, soft leather, which prevents the pad from sticking in the wrong place when the gun is thrown quickly to the shoulder. It saves a bruised shoulder and headache, makes shooting a pleasure and offers an improvement in shooting. Write to J. R. Winters, Clinton, Missouri. Mention this paper.”

--

If you're interested in other moments from long-arm history, take a peek at:

Leave a comment (all fields required)